This episode was recorded on the land of the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin nation. We pay our respects to their elders past, present and future.

Richard: Hello, and welcome to another episode of Precisely Property. I’m your host, Richard Temlett. I’m excited to have you with us today. If you’re here for the first time, thank you for joining us. I encourage you to listen to our previous episodes where we discuss all things property with a focus on dynamic discussions with industry leaders. In this episode, we’ll be discussing affordable and social housing with Nicola Foxworthy. So, sit back, relax, and let’s get started.

Nicola Foxworthy has over 20 years’ experience in affordable housing delivery across executive roles in community housing and the public sector. She specialises in policy, funding, strategic planning and stakeholder engagement with extensive cross sector networks. Nicola is the Founding Director of Imagine Housing, a sessional member of Planning Panel Victoria, and a Co-Founder of Middle Ground Housing, an incubator for cooperative housing solutions. Welcome, Nicola.

Nicola: Thanks, Richard. Thanks for having me.

Richard: In today’s episode, Nicola and I will explore the role of affordable and social housing, breaking down key definitions and why this is relevant to both the public and the private sector. We’ll share insights on the evolution of the industry, funding challenges, and lessons from major initiatives like the Big Housing Build and the HAF. I hope we’ll get a chance to discuss what the future looks like and the opportunities to support emerging housing needs.

Nicola, as I mentioned at the beginning of this session, for this season, I’m going to kick off each podcast with an icebreaker. So, the question I’d like to ask you today is as follows. If someone met you for the first time, what’s one thing you’d want them to know about you?

Nicola: It’s a good question. I reckon I’d like people to know that what they see is pretty much what you’re going to get. Pretty straightforward. I try and be really open and generous in sharing my skills and my experience and my point of view. And I’ve, across my career, had lots of opportunity to learn, to work with really great teams. And at points in my career, particularly as a sole parent, at times when I had limited capacity to put in extra hours or do any of those things, so I feel like I’m the beneficiary of that and, I want to pay that back. I want to pay it forward, really. It might not be the recommended way to run your consultancy, but I’d rather be collegiate and share that experience, than withhold it to charge for it at some point. I guess that, in my experience, often leads to better work and more interesting discussions and I guess the whole sector is trying to develop and emerge. So, it’s a contribution into that. But it does mean, for any of your listeners, if you’ve got a question you think I might have something to contribute, give me a call, shoot me an email, really happy to chat.

Richard: I was going to say, first of all, that’s a great answer, but certainly, I think that’s why you and I have connected in terms of sharing those views about collaboration and sharing insights. And so, yes, our listeners, please do, reach out. I’ll put all the links into the show notes as I always do. I’m sure you’ll find today that there is a wealth of knowledge to be unpacked. And, certainly, in my experience, Nicola is at the forefront of this.

Alright. Before we get into the themes or the agenda for today, could you please tell the listeners, and I suppose myself too, a little bit more about Imagine Housing and your role in the organisation.

Nicola: Sure. Look, Imagine Housing is a consultancy that I established to provide specialist affordable housing advice into the industry. There’s not actually a lot of that advice easily available, particularly in Melbourne, or across Victoria. I mean, it’s probably true right across Australia, actually, but my main focus is here. Imagine Housing looks to help clients understand where they fit in what is effectively an emerging industry. It’s not a fully-fledged industry. There’s a lot of moving parts and a lot of change going on. So, in my experience at the moment, there’s a lot of organisations, both government, quasi government, not for profit and commercial players trying to work out where they fit. So, Imagine Housing is actually a vehicle to help people unpack that and to work out what, when, and how they might want to play and what role suits for them. And right now, that emerging nature of the industry is, there’s opportunity to shape it. There’s an opportunity to direct how things will emerge. People are taking that on and wanting to work out where they sit inside of that. Imagine Housing also has taken a particular role specialising in innovative delivery models, but particularly those models that are either low subsidy or no subsidy because I think that’s an emerging part of the market that’s really underbaked at the moment. And because it’s not been a problem for as long as the deeper subsidy options are, there’s not actually that much thinking in the space yet. So, it’s one of the things that we might get to as we discuss going through.

Probably worth me giving a bit of a ‘where have I come from?’ in a career sense. My career is probably pretty checkered. At one point, I was a hotel manager, believe it or not. I can’t believe that anymore, but it’s true. Anyway, after some time working in other places, I worked out that my interest in housing is a fundamental foundation for pretty much everything else both from a personal point, from an individual point of view, the foundation for your life. If you don’t have access to a stable housing it makes a pretty big impact on what else you might do with your skills and talents. But also in terms of the foundation for community, for economy, like for me, it’s a big picture thing. It made me realise that I was a big picture thinker. That sent me back to university, did a policy degree, did a planning master’s and then started working in state government in strategic planning, integrated transport land use planning. So, bigger scale planning. So, metropolitan strategic planning, growth area planning, precinct planning, that sort of stuff. And then, I was there for 15 years or so across Melbourne, 2013 was where I started. That gives you a timeframe for what was going on. Yeah, Melbourne at 5,000,000, Plan Melbourne across there. And then in 2009, I moved to one of the community housing associations as Program Director. So, that had me involved in the delivery of affordable housing programs and by its nature obviously required a deep understanding of the funding scenarios and the ecosystem that that work existed in. Having done that for 10 years, I have now stepped out and started my own consultancy, bringing all of those specialties together. In my experience, the best jobs I’ve ever had have drawn together, a number of different things into one space. It gives you a unique perspective on what’s going on and it’s often a very valuable one.

Richard: Well, thank you for that. I knew a large amount of that, but I hope our listeners can understand and hear why I think you are ideally placed to talk about affordable housing, social housing, housing affordability, and start a really good education piece. And that’s going to be the first part of today’s discussion because, as we were chatting offline and certainly in the work that I’ve done, there are different definitions of affordable housing across Australia. I don’t believe it’s very well understood or very well applied, and I act for a lot of the financiers. I have the privilege to do that. And I often talk with them, and that’s one of the first things that they’re after. It’s basically getting that certainty on what those definitions are so that they can accurately and correctly price the risk. And so, let’s start with some of those definitions, as a bit of an education piece to try, I suppose we could even describe it as demystifying the industry because that is honestly, when I leave some of those meetings going, the hardest part of this is actually understanding what specifically we’re talking about. So, the first one, let’s talk about why should everyone care about affordable and social housing.

Nicola: One of the realities for affordable housing in its broader sense is that it takes a whole raft of stakeholders to deliver. Like, it’s not a simple, it’s a very complex ecosystem. And so there’s a range of stakeholders with a huge range of skills going on in there. It’s touching federal, state, local government, community housing providers often, financiers, investors, commercial developers, commercial builders. There’s a whole range of people in there. I think as we increasingly recognise there is a problem, like, if I go back 15 plus years, in fact, maybe more than 15 years, some of these discussions, you’d actually be convincing someone that there is an issue around supply of affordable housing. I don’t think we need to do much of that anymore. I think it’s a recognised deep issue, and the importance of the issue is much better recognised than it has been previously. I think, in fact, probably crescendoing to an understanding of the degree of crisis that we might be in. But that means that some of those players who have had peripheral roles previously are understanding that there is a role for what it is that they do and that’s particularly true for the commercial players and the sector developers. It’s pretty hard to have a conversation about the development of large-scale residential development without a discussion of affordable housing somewhere in the middle of that. And even at low scale, at local government level, the level of interest is so strong that all of those commercial players are having to grapple in some way with what’s going on. And so, I think that means the understanding of what we’re talking about, why it matters, who it affects, who we’re talking about housing, what the costs are becomes much more critical to the conversation for what used to be a commercial mainstream player who didn’t see themselves having a role. I think that shifted quite significantly. I think people understand there is a role.

The other thing that I think has changed quite significantly is I now interact with a much larger range of people who are not directly involved in the community housing, social housing delivery bit of it immediately, but who are really concerned about the impacts of that, not just on individual households, but on the functions of communities, on the functions of economies, and that broadens the conversation. So that means that players who previously would have gone, even if they recognised that affordable housing might be an issue, would go, yes, it’s an issue, but it’s not one that I have to deal with. Many, many, many more people these days will go, ”yeah, I think it’s a real problem.” I think it changes the way that things that we’ve taken for granted are actually operating. Like not least of which, my kids can’t house themselves. The level of direct interaction with the implications and the impacts of a lack of affordable housing is actually hitting home for a much wider range of people now. So that has people who are otherwise commercial players paying more attention and being more interested, and not just from a business opportunity point of view, from a ‘we all want our world to work’ point of view.

Richard: Great. Well, let’s do some of the definitions because, again, I’ve definitely observed that there’s a huge amount of misunderstanding in the industry. And an on the top of the list is the distinction between affordable housing and housing affordability. What are your views on that and what would you like the listeners to know in your experience?

Nicola: Look, I think that there’s a bunch of terms like that. Getting really crisp definitions across any of this is challenging. In fact, there are a range. I think what we’re talking about here is trying to get some basic concepts in place so that people have got a common starting point for what they’re talking about.

In general terms, when people talk about housing affordability, they’re actually talking about the cost of market housing relative to income, right, relative to household income. It’s a very broad term. It’s most commonly used in terms of first-time buyer market housing purchase rather than rent, and it kind of gets used. There’s all sorts of measures of housing affordability in terms of it’s a measure of how the economy is moving in many ways. So, probably worth pointing out that any of the things that we’re talking about when we’re talking about affordability of any kind, we are actually talking about the relationship between the cost and the income. You don’t get an affordable housing outcome until you’ve addressed that in situation. So, a cheaper house is just a cheaper house. It’s not an affordable housing outcome until you’ve connected it to something that’s affordable to the house to your target household. It’s a useful frame for thinking about why there’s so much variability when we talk about affordable housing. It stretches out because you have to bring those complex factors into play. Even the broader term, housing affordability, whether something’s affordable for an individual household or not depends so much on personal circumstances. Did you just inherit $3,000 from your grandma? Like, you know, what you can afford. They’re not nice easy definitions in that sense.

To come back to your fundamental question here, the difference between affordable housing and housing affordability. Housing affordability is that broad term applies to a whole lot across the market but usually to the cost of market purchase market housing as a purchase rather than as a rent, and its interaction with income. Affordable housing is, I will actually try and refer to it as capital A, capital H, Affordable Housing. Being a term that refers to housing that is usually non-market housing, to make it affordable, to make it no more than 30% of a household’s income. And it’s usually targeted and allocated to certain cohorts to address an affordable housing need.

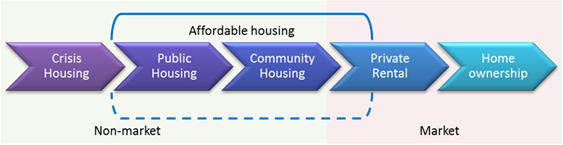

Richard: Gotcha. Then let’s extend that a little bit further. Social Housing. Where does Social Housing fit along the spectrum?

Nicola: Yes. So, it fits under an umbrella of Affordable Housing. So Affordable Housing includes a category called Social Housing and to really mess with your mind, that Social Housing category is also a subset of Social Housing is Public Housing, being Social Housing that is delivered directly by government, that’s Public Housing. The defining feature for Social Housing is generally understood to be a rent model rather than a different kind of housing if you like. Social Housing will generally be delivered either by state government as Public Housing or by the Community Housing Sector as rental housing, not purchase housing, and will have a rent model that is set at a specific level, usually no more than 30%, sometimes 25%. Public housing will be 25%, for example, of household income.

What that means is if household income changes over time, there’s a regular review process and an ability to ask for a reassessment so that your rent is never more than 25% or 30% depending on what program you’re in. And that’s a distinction between social housing and other forms of affordable housing. So that rent model that varies with income, that’s a social housing model.

Richard: Sure. Do you, by any chance, have any infographics?

I’m thinking that just listening to what you’ve spoken about, I know we do it. I may well put an infographic where it’s got a dichotomy of all the different housing typologies because, we call it the housing spectrum, and it’s definitely as you’ve very well described. But I know that there’s people out there that probably are better with the visual rather than the audio. And so, if you’ve got one, if you could please share it. Otherwise, I’m certainly happy to post one ourselves. I know and why I’m touching on this is because I’ve seen different variations of this across different states, and therein lies some of the issues already. So if you do have one because I know down the line, we’re going to talk about things like the dwelling diversity and affordable housing reports and the work that you’re doing there to quantify the depth of demand and look at the need in certain areas. But it’s important to actually address what need and what segment of that market is being addressed.

Nicola: Yeah. I think that’s right. I think one of the realities in the way that affordable housing programs and the variance between a social housing program and affordable housing program is that it’s responsive to the incomes of those households. So social housing programs are increasingly focused on very low or low-income households, so the lowest two quintiles in the income distribution. Affordable housing is often targeted to moderate income households, so the third quintile in the income distribution, and that is to do with capacity to pay for the cost of that housing. So a discount to market rent in some instances is enough for a moderate income household to be able to afford that rent, where the level of discount to a market rent required for a very low income household to be able to afford the rent is much, much deeper so that they end up in different programs and targeted in different ways.

Richard: Well, I’m glad you started talking about that subsidy because that is one of the things that I know both you and I separately have done a lot of work on. We’re basically explaining to all tiers of government that both affordable and social housing actually need a subsidy. So, can you explain a little bit more? I know you started addressing it, but why does it need a subsidy?

Nicola: Before I do that, I’m going to go back one step and just note that certainly in Victoria, in New South Wales, I’m pretty sure in Queensland also, there are definitions of affordable housing that have now been embedded into planning systems. And I think for your listeners, that’s actually an important element for us to tease out a little bit in the definitional sense. In Victoria, for example, the PNE Act now defines affordable housing and it gives local government a role in facilitating the delivery of it. There are no mandatory controls in Victoria but there is a defined focus in what it is a local government might do.

The definition that sits within the planning system is a broad one and I think that’s a good thing. It’s rightfully a broad one because there’s lots of different scenarios that you want the definition to be functional in. But it does, from a developer’s point of view, give you at least a benchmark starting point for understanding what requirement might exist if somebody’s saying to you, you need to deliver an affordable housing outcome consistent with the planning act and mechanisms in the planning system. So the definition that sits in the planning system is “housing that is appropriate to the household and to the needs of very low, low or moderate-income households.” And those income definitions are set each year. The minister gazettes income ranges that apply for each of those quintiles where the costs of housing, and that could be either rent or purchase, so it’s not specific it doesn’t exclude either, are no more than 30% of household income. And that takes you back to that extra complexity in the makeup of that household and what’s going on in there and what that looks like.

But it is a fundamental benchmark that can be used and for a developer or a landowner who is being asked to assess an affordable housing opportunity, that’s what they’re being measured against in a planning system sense. There are other programs that will have their own funding requirements, priority cohorts, benchmark deliverables. But this one I think is the one that most people grapple with most often. Understanding what it is you’re being asked to do, you are being asked to come up with housing outcomes that are affordable to cohorts whose income are no more than that moderate income limit and that are available to them at a cost that’s no more than 30% of their income. So, it does give you , at least in a rental sense, a price point you can work with. It’s slightly more difficult to work out what that means in a purchase sense, but you can come up with ballpark discussions around what that means.

But it gives you a kind of…you can see where in the market you’re trying to sit. That takes us back to your first question now, which was what’s the subsidy about? I think in most locations, particularly in higher value locations, the maths on making something affordable in that 30% of household income, for that within those income bands would tell you that the market housing product can’t be delivered at a price point that is affordable within 30% of those households’ incomes. And actually if we’re going to deliver affordable housing for those households, then there is a need for subsidy. So that’s what that subsidy piece is. It’s the gap between what the market cost is and what that household can reasonably afford to pay and the benchmark of somewhere between 25 and 30% of your income being accepted. There’s a general acceptance that that’s a reasonable benchmark that you could expect someone to pay on their housing cost. And we also have a term ‘housing stress’ that refers to households who are paying more than 30% of their income on their housing cost. And it’s generally recognised that housing stress is particularly concerning, particularly problematic for households that are in the lowest two quintiles, maybe a bit of the third as well. Because if you’re spending more than 30% of your income, and your income is that low, in the very low or low-income categories, you don’t have enough money left over to do all the other things that you…I was going to say discretionary. They’re not discretionary things. You need to eat. You need to transport, education, health, all of those other things that go alongside living. So, a kind of recognition that paying for very low and low-income households, paying more than 30% of your income on housing costs is very likely to be causing stress on all the other parts of your budget and life generally.

Advertisement: Quickly interrupting this episode to tell you about Charter Keck Cramer. Charter Keck Cramer is an independent property advisory firm with offices in Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane and the Gold Coast. Through our collaboration with Andersen Global, we connect with over 18,000 professionals around the world. We provide strategic property advisory services spanning multiple market sectors. Our Advisory team provides specialist advice across transaction management, tenant representation and lease negotiation, strategic portfolio reviews, development advisory and more. Complementing this, the Capital division advises on structured property partnerships connecting property owners and tier one developers.

Our extensive Valuations coverage includes prestige residential and greenfield development markets, together with all commercial asset classes. Quantity surveying is at the core of the Projects team, ensuring cost control from planning through to post construction. And our Research team delivers property data and analytics across the residential living sector, along with expertise in strategic land use planning and urban economics. With specialists across a diversity of sectors, Charter Keck Cramer is your trusted property advisor. Now let’s get back into the episode.

Richard: Before we shift gears and then get into the evolution of the industry, the final definition that I’d like to explore a little bit more with you is community housing providers. So, what are community housing providers?

Nicola: Community housing providers are not for profit organisations that develop, own, and manage housing, targeted to very low, low and moderate-income households. As not for profits they can actually do other things to generate funds to be able to deliver that mission. So, some of them are doing all sorts of things, running real estate agencies, body corporates, owners corporation businesses or owners corporation management businesses, full price rental housing, all sorts of things to generate. But in the nature of a not for profit, they are focused on serving the needs of the eligible household. Anything else they’re doing is generation of funds to be able to support delivery of that mission. Community housing providers are really tightly regulated. As a business they’re regulated through the normal ASIC, those sorts of things. As a charity they’re regulated through the ACNC, the Australian Charities and Not for Profit Commission. And as a registered housing provider, they’re regulated either through a national system or Victoria has a slightly separate but fits within the family of regulation, there’s a Victorian housing registrar who oversees the function of community housing, Victorian registered community housing, operators. That regulation is incredibly important because it means that the subsidy that those organisations have access to is tightly captured in a regulated system and able to be reused and recycled against mission over time, which is really important because the affordable housing need today won’t be the same as the affordable housing need in the future. Housing assets come to the end of a useful life so you need a way of recycling and reusing and that regulation is a really great way of making sure that it’s tightly managed within that system and I guess anyone who’s putting subsidy into that system can have the confidence that that’s what’s going on. Mostly that subsidy is coming from government, but sometimes it’s coming from, a planning requirement, planning mechanism or there are other ways that subsidy comes into the system. So, understanding the nature of that capture and the requirements to use that well is an important element.

One thing that I think is really useful for your listeners to understand is that the community housing sector does not receive ongoing operational funding just to exist. That’s not the structure of the sector. The structure of the sector is designed actually to be able to use its own resources and its own assets to be self-funding, if you like. That makes all of the community housing operators very reliant on the rent revenue that they receive and, of course, that rent revenue is curtailed because it is for a good chunk of what they’re owning or managing a social housing rent. So, it’s 30% of income and 30% of income for someone who’s on Centrelink payments is pretty constrained. Coming back to the notion of the subsidy that is required, state and federal governments have for a long time provided subsidy funding programs for that subsidy, and regulated registered housing providers are the key focus for delivery of those sorts of funding rounds. So that’s mostly where the subsidy is coming from and those organisations are bidding for. It’s a competitive process, bidding for and applying then those funds into the development or the purchases or the maintenance of the housing that they already own. It means that community housing organisations are exceptionally good at feasibility. They actually need to know what all the variables are to be able to deliver something that allows them to meet the requirement of the funding requirement. If what you’re doing is saying, yes, we’ll take this level of funding and we will deliver x number of social housing homes for the next 30 years, you need some pretty tricky maths to be sure that you have the wherewithal to be able to do that. I think from a commercial developer’s point of view, that’s worth knowing that the people that you work with, if you’re talking about an affordable housing delivery product as part of a bigger development, the people that you’re working within the bigger housing associations or providers, they will have a very firm understanding of development feasibility. They are for purpose developers. That’s what they’re doing. In fact, the sector would tell you that they’ve been delivering affordable BTR (Build to Rent) for a very long time. That’s what they do. So, I think those skills, recognising those skills exist and kind of opening up to a professional and experienced discussion about what that means if you’re haggling over what’s actually possible. They’ll understand your feasibility and you’ll understand theirs. You’re doing the same thing, you just have different outcomes that you’re trying to embed into what your feasibility is telling you and the decision making processes that flow from there.

Richard: Very interesting. I certainly wasn’t aware of how sophisticated they were with the feasibility side of things. I’ve dealt with some of them, and I have been impressed. I didn’t realise, I suppose it makes sense of the requirement that they’d have that level of rigour in the feasibility side of things.

Nicola: Probably worth me highlighting that that won’t be true for every housing provider. There’s a real range of housing providers that go from very small organisations that are essentially really skilled and very specialised tenancy managers for particular cohorts or in particular locations right through to, it’s the bigger ones that have got the capacity, and they’re regulated to have the capacity to be able to manage financing and development risk. The feasibility, all of those things that go along in that space.

Richard: Look, let’s jump into, I’m keen to talk about the Big Build and the Housing Australia Future Fund. I know that you’ve been involved in some of these projects. And, again, we’ll never breach confidentiality and things like that. But one of the things I would love for you to do, given this is an education piece, is to talk about some of the lessons learned that you feel the industry, both public and private, need to be aware of given what’s happened more recently with that significant or even unprecedented level of funding. What were some of the lessons learned?

Nicola: Yeah. Look, I think this is probably from a community housing sector point of view. It’s probably an old lesson, but I think that the scale of funding that has been available in the last little while. Victoria is a pretty good example of that. The Big Housing Build at state level and then at federal level, the Housing Australia Future Fund money. There’s a couple of things going on in there. One is it’s a big quantum of money over a really short time that has the whole industry having to scale up really quickly to be able to grapple with that. It’s a competitive process. If you’re not in it, you can’t win it. And for organisations to be able to manage growth, recycling, change, the bumpiness of that kind of funding process is actually really challenging.

Richard: Just with that for some of our listeners who might not have the level of expertise as yourself, could you briefly describe the Big Housing Build and then the Housing Australia Future Fund, and what that is, why that’s relevant?

Nicola: Yeah. And look, I think the other thing that I should touch on is that both of those funding processes represent a different approach to the way in which subsidy is being introduced into the affordable housing sector. I think historically, most of the funding used to be capital funding. Increasingly, the funding that’s available is availability payments. So, payments to a provider to make sure that affordable housing is available. It’s meant to address the shortfall.

Richard: The subsidy?

Nicola: Yeah. That’s right. It’s a regular ongoing subsidy for a period of time to address the shortfall that occurs when a household can’t pay the market rent for a product. So, in the last little while, across the last maybe five years in Victoria, the Big Housing Build has had substantial investment. The biggest investment in social and affordable housing that the state has seen for a really, really long time. It comes off the back of a couple of decades of shrinking funding so partly it’s playing catch up. And I guess it also reflects the change in relationship between state and federal governments where in the 80s, some of the 90s, the function of our state federal hierarchy and the vertical funding challenges that go on with GST and the like, that the arrangements that funneled money from the feds to the states under a Commonwealth State Housing Agreement and then later a broader housing agreement, they’ve all changed around a little bit and that has resulted in changes to the ways things are being funded. But the biggest shift from, the bit that matters is that it shifted largely away from capital grants and to availability payments which means that the operator is being expected to be able to get private finance and use the availability payment to be able to…

Richard: Close the gap?

Nicola: Yeah. To close the gap. To be able to service the debt against that. That’s a pretty significant change to the way that that funding has previously been done. And, again, it takes me back to how sharp the pencils are for all of those bigger organisations that are working in that framework because they need to know that they can fund a 30-year mortgage debt against property. And all of that’s happening in a deeply regulated sector in a number of ways to protect the investment into that housing outcome. So, all of those risks and whatnot are being carefully assessed on the way through. But that does mean across the last little while at Victorian state government level over the last five years, the Big Housing Build pumped something like, I think, $5.4 billion into social and affordable housing outcomes. Some of that delivered directly by states, a good chunk of it delivered by community housing organisations.

At federal level, after a lot of argy-bargy and backwards and forwards, we now have a Housing Australia Future Fund. So, it’s effectively a fund that is hypothecating the return on that fund to delivering housing outcomes. If you’ve been following any degree of politics, there’s all sorts of discussion about whether that’s good, bad, or indifferent. From my perspective, it leaves me…I think that the way that it’s been working thus far is still very new. We’ve only had one round go through. It’s still pretty clunky, I think, and there’s a lot of things to be ironed out. But one of the big challenges is the lack of predictability about where the subsidy comes from. And that’s an issue for everybody. It’s an issue certainly for the community sector for any of the housing providers. But it’s also an issue for any of the private commercial developers trying to work out how to play in the field. And what it means is every time a funding round drops, there’s a huge flurry. All sorts of people need to ramp up their capacity to operate in that system very, very quickly. That’s true for the community housing sector. It’s true for the private players that are trying to play into that space. It’s actually true for the financiers and all the other people, the peripheral stakeholders in there. And, for example, the first Housing Australia Future Fund got bids for projects three times more than the money that was allocated. That at its bluntest means that two thirds of the energy that went into putting those bids together is possibly wasted. It won’t be entirely wasted. Some of those bids will come back up, but there is a limit to how long you can hold a shovel ready project to put back into the next funding round particularly when you don’t know when it’s going to happen. The other issue I think, so there’s issues in the mechanics of what you can bring to the table. There’s issues in the bottleneck that it causes when everybody’s bringing it all to the table at the same time, not just in the funding round, but then in the delivery.

So, what we have is now a funnel of a whole lot of projects that have all promised the same thing. They all need to be delivered in the next two years or whatever the promises made in the funding bids are. Notwithstanding that there is pressure on getting stuff on the ground as quickly as possible, but that it’s the bottleneck that I’m referring to, it’s problematic and it’s potentially a little bit wasteful. You’re paying more for the same thing because you want it all at the same time. But it also is problematic for two other reasons. One, in a capacity building sense for the sector, you can’t actively plan for how you manage your capacity growth when what you’re actually being asked to do is to grow and shrink and grow and shrink and grow and shrink. So that’s challenging for the sector.

Richard: In terms of any other lessons learned, obviously, there’s going to be future funding rounds. Given your experience on the ground and in the first round, what could be done differently or better to improve the outcomes and get better results?

Nicola: I think that some of this thinking is already going on, like the advocacy from the sector into both state and local government. I think within Housing Australia itself, I’m pretty confident there’s a lot of thinking going on about how you create, at the very least, more predictable funding rounds. The other thing that the bumpiness stops is the value engineering.. It makes community housing organisations not great partners because they don’t know what they want, when they want it, how much money they can pay for it. And everything’s subject to successful funding out of a bid round or whatever it is. That’s a real handbrake on deep partnership, real partnership, where the players are able to bring their specific skills to the table in ways that are feasible and work for them. So, in that development economic sense, uncertainty is the thing that amps up all the costs. Well, here we are in a system that still embeds a good chunk of uncertainty into the process right now. So as I say, I’m actually really optimistic that the future fund is a pathway to be able to get much more certainty about what funding, when funding, what process, what does that look like. In my most optimistic, I can imagine a system where it’s possible to balance out delivery risk and I guess capacity of organisation to be able to deliver well ahead of individual specific bids because, actually, that’s the thing that would free people up to be able to go and partner to create long enduring partnerships with volume builders, with developers, with landholders in the longest sense of the world and then be able to value engineer the product. If we’re actually looking to squeeze maximum impact out of every dollar, every subsidy dollar that’s coming into the system, to my mind, we have to be able to go there. It’s challenging and there are risks and regulatory frameworks that need to be managed. You can quite understand why government is very keen to understand a lot of detail about projects. I suspect we’re still in a frame where there’s double checking of stuff. So if you think about the regulation that comes from ASIC, the regulation that comes from the ACNC, the regulation that comes from the relevant housing registrar, the regulation that comes with funding requirements and deeds, often there’s overlap in there and I think there is a smoother way of working our way through there so that we’re not double reporting or at least we’re using the same reports to…that’s increasingly true actually. People are able to use the same reports to multiple players. In an ideal world, we’ll have a system that has streamlined enough that you’re not doing that and that it’s a pathway to much more predictable and committed funding processes that will underpin true partnership and value engineering for the demand that we’re seeking. If we’re going to meet the level of the scale of demand that’s out there, we’re going to have to and we’re going to have to do it in a way that brings the private sector in as key partners because let’s face it, the vast majority of residential development in Australia is by the private sector. And I can’t actually see that, I don’t think that would change, even with much more significant funding into the sector, even with more direct interaction of governments. It’s not going to change who’s best placed to volume build. It’s very unlikely to be anyone other than the private sector. So, we need to work out the roles, the responsibilities, the regulation that will actually make that work as smoothly as possible.

Richard: Look, final question for today. The DDAH reports, the Dwelling Diversity and Affordable Housing reports. I know that you do some of them, and I’ve also had clients come along and go as part of the planning permit application councils asked us to do that. In maybe 30 seconds, what is it and what do you do as part of that report?

Nicola: Yeah. Look I think that those assessments are really part of a drilling down into which cohorts, what they need, where the shortfalls are. So, very much like a big sense of a housing strategy, understanding who’s in this area, who’s not in this area, why are they not in this area, who do you want in this area. So, I think those assessments are really being able to flesh out not just a broad sense of ‘we’ve got an affordable housing problem’ but in this location, what is the problem? Who’s affected? What does that mean for local communities and for local economies? Who do we want to attract into this area? Who’s in need of what support? And what funds are available to make that real? Because you can write all the assessment. Certainly, I don’t think we need to do a whole lot more work on what the need is. There is a lot of evidence out there about what the need is. We might need to do that sort of applied sense of what’s the specific need in this LGA, in this precinct given the ideal role of the precinct that council’s trying to underpin. So, if you’re trying to get an employment precinct up, you might want to think about key workers. If you’re trying to get a health precinct up, it might be more appropriate to think about a social housing ask given what’s going on. So, there’s some of that contextual stuff that matters. My view is that there is an awful lot of data around how deep the need is. I think that the point of doing that work is then to be able to draw out from there what are the options to deliver them. So, understanding what level of subsidy is needed against what kind of housing outcome. So, a planning scheme can say or a planning permit can say 5% affordable housing. But does that mean you are being asked for 5% gifted to a housing provider to use as social housing or are you being asked to provide 5% as key worker dwellings for 20 years? The feasibility impact of that will be significantly different. Those housing assessments should be part of the jigsaw to put together what’s actually being asked, why it’s being asked, and what are the tools that will be needed to deliver. I think councils are having to be really careful about how they embed requirements into permits or pressing planning processes so that they are actually deliverable because requiring something that requires subsidy when there’s no subsidy around is actually really problematic for everybody. There’s a discussion there about, and I think that discussion has been pretty clunky for the last little while, and I think it’s starting to get a bit more sophisticated now. So now most councils and most of the bigger developers are much more able to have a refined version of that. I’m not saying it’s sorted and easy. It’s clearly still challenging, but it’s better than it was. And I think that we’re in that process. We’re starting to stretch out what that might mean and what tools might be required.

Richard: Great. The final question that I will ask is, Nicola are you able to let us know what the future looks like?

Nicola: I think the future is a mix of much more sophisticated delivery of what we’ve already got. So, the Social Housing, the Affordable Housing system, the players are getting much better at doing that. I think the bit that’s emerging is a broader understanding of housing need beyond what has traditionally been understood as the houses in need, if you like. We have an increasing cohort of middle-income people who are locked out of home ownership, which means in our market that they’re a bit stuck in a private rental market that was never designed to be long-term. Part of the work that I’ve been doing, particularly with middle ground housing, is exploring other tenures, other options. It’s a different kind of housing product that is designed to provide long-term secure housing that is not your wealth producer but is offered at a lower and has a level of affordability baked into it. That means that you can do your wealth investing somewhere else. This won’t be it, but there’s an opportunity to do that.

But it’s changing the way that the Australian market has thought about housing and wealth both, and retirement potentially. Testing some of that. I think that there’s some emerging markets in that space, and I think we have a growing number of people pretty desperate for an option that is something different to short-term private rental and long-term home ownership that gives them some control over what their housing option looks like and where their investment choices are.

Richard: Great. Well, we’ve got through a lot today, so I wanted to thank you very much for taking the time to come on. I’ve really appreciated sharing various ideas with you. We’ll obviously have all your links and information to both yourself and your website. And I encourage our listeners, I’m convinced that you’ll be reaching out in the short or longer term to Nicola, given where we are with the housing crisis and the planning changes and the requirements for affordable and social housing. Thank you very much again for your time, and hope to have you back on the show soon.

Nicola: Thanks, Richard. really appreciate the opportunity.

Richard: Hi, everyone. I hope that you really enjoyed listening to what Nicola had to say with respect to Social and Affordable Housing. There’s obviously an enormous amount to get through in this show and we’re still on very much a learning curve and an education of the industry. But three things that I would like everyone to take away from today’s show, certainly that I’ve had reiterated to me over a number of periods of time, but also that were highlighted in the show are as follows.

The first one is we need consistent definitions of Social and Affordable Housing, and they need to be consistently applied across Australia. It’s incredible when I speak with different developers or LGAs or even the state departments, and they have this especially in the affordable housing space, different definitions of what they are. And that’s very difficult to apply, not just for the developer, not just for the council, but also for finance. Having a consistent set of definitions is absolutely critical for everyone in the industry so that everyone is referring to the same set of criteria.

The second key finding from today is that affordable housing needs a subsidy. I can’t emphasise that enough, and it’s really important that government at all levels understands that if we’re doing housing that is below market pricing or market rents is a gap that needs to be filled. And that is the role of governments to fill in the form of some sort of subsidy. There’s different ways that the subsidy can occur, but, really, that’s absolutely critical, and the government does an important role and it is doing it very well in certain areas. But, again, it needs to be consistently applied and the industry needs to be a little bit more educated on the subsidy. The forms that it can take, and how much it will be because it will be very different in different locations based on the current pricing and rents in those markets.

Finally then, I’ve spoken to a number of financiers who are very attracted to social and affordable housing. They really like the asset class in terms of the risks and returns that they could potentially achieve. But what they have certainly told me in the feedback and even looking at the Big Build in Victoria, is that they need programs and models that are consistent and that are replicable or repeatable. And why that’s important is because once finance and once the different stakeholders understand how to pull the documents together, how affordable or social housing will work, how the subsidy will be provided or applied, it can be replicated or repeatable at scale. And that’s what a lot of the financiers or a lot of the investors who view this asset class as infrastructure rather than real estate want. It’s replicable, and repeatable at scale. That’s just some food for thought.

Again, please reach out to either myself or Nicola if you’d like to talk a bit further about either social or affordable housing. Thanks very much. Bye.

Thank you very much for listening to this podcast. If you enjoyed the episode, please make sure to subscribe to our podcast so you never miss an episode as we’ve got more exciting content coming. We’d love to hear your thoughts. Please leave us a review on either Spotify or Apple Podcasts as it really helps us to grow. Also, follow us on Instagram at Precisely Property for updates and join the conversation. If you’d like to get in touch with us, subscribe to our newsletter via our website, charterkc.com.au, or write to us at podcast@charterkc.com.au. Lastly, if you found this episode interesting, please share it with your friends and family.

Thank you again for listening and stay tuned for our next episode dropping in two weeks’ time, plus bonus content also on the horizon.

Disclaimer: Precisely Property is a podcast presented by Charter Keck Cramer and is for educational purposes only. Nothing in this podcast should be taken as investment or financial advice. Please engage the services of an appropriate professional adviser to provide advice suitable to your personal circumstances. The views expressed by our podcast guests may not represent those of Charter Keck Cramer.