As featured in The Australian Financial Review by Michael Bleby

20 November 2024

When developer Pace completed a two-tower unit development in Melbourne in September, it had still 72 of 313 apartments unsold.

The problem for the privately owned developer was that the apartments it was selling in inner-northern Coburg cost more – up to $50,000 more – than existing apartments in the same Pentridge Prison urban regeneration precinct, Pace managing director Shane Wilkinson said.

Surging construction and financing costs have made new apartments more expensive to develop just as those same high borrowing costs – combined with a cost-of-living crisis – are pushing down prices of existing homes.

The Pace 3058 apartments, selling for between $8700 and $10,000 per square metre because they were built in what he called the old world – “where pricing was still reasonable” – would need to sell at $11,000-$11,500 per square metre to justify a new development today, Mr Wilkinson said.

“The difference between the pricing of existing stock and what we would need to get to make a project feasible on an off-the-plan basis is in the vicinity of 20 per cent,” he told The Australian Financial Review.

There’s always been a price premium for new apartments, which like new cars cost more than a secondhand model, but economists say surging building and finance costs have widened that gap more than ever.

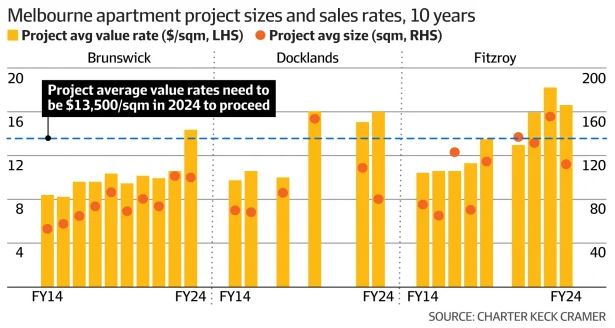

“In Melbourne in 2019 a new 60-square-metre apartment used to sell for $600,000 and now needs to sell for around $780,000,” said Richard Temlett, the national executive director of consultancy Charter Keck Cramer.

Developers just won’t develop if it means they won’t make money.

Planner Alice Maloney

While Melbourne is the market hardest hit, it’s also a problem in Sydney and Brisbane.

“The difference between new and established units is too wide for buyers to be enticed to purchase new dwellings,” Mr Temlett said. “The prices of established units need to recalibrate upwards by around 15 per cent for new stock to be accepted by the market at current economic price points (around $13,500/sq m).”

That is going to worsen Australia’s chronic housing shortage. Costs won’t fall – although the rate of gain is likely to slow – and developers will hold off new housing projects until established housing prices rise enough to make new off-the-plan homes competitive once more.

“Developers just won’t develop if it means they won’t make money,” said Alice Maloney, a director a planning consultancy Ratio Consultants. “Only the high-end, luxury developments are stacking up financially at the moment.”

Pace is still selling apartments in the Coburg project and the number of unsold units had fallen to 47, said Mr Wilkinson who said his apartments were higher quality than the older, surrounding apartment stock. Having paid out the bank loan that funded construction, he has taken out a so-called residual stock loan with non-bank lender Qualitas while it sells the rest.

Residual stock loans have become common in the lifecycle of a development, as they are often needed at the end of a project to fund the developer while they sold off remaining stock, Qualitas managing director Andrew Schwartz said.

The problem is the volume of development is well down.

Qualitas managing director Andrew Schwartz

“Anyone substantial in the private credit market will do that type of lending,” Mr Schwartz told the Financial Review. “It’s become quite a deep and competitive market.”

But with fewer developers constructing projects, there is less residual stock, or inventory, to finance.

“We would love to do more,” Mr Schwartz said. “The problem is the volume of development is well down.”

A number of factors make the imbalance in pricing between new and old apartments worse in Victoria than other states. These include the government’s better apartment design standards, which set minimum sizes and design standards in 2017 and were updated in 2021.

Rising land taxes and compliance costs in the private rental market to increase the quality of accommodation for renters were also prompting investors in Melbourne to sell, increasing the pool of apartments for sale, real estate agents say.

“We’ve seen a number of investors leave the market, selling their investment properties,” Nelson Alexander agent Peter Varellas said.

A further hurdle was the Victorian government decision in October to slash stamp duty on off-the-plan for new apartments, units and townhouses, for 12 months, to stimulate more development. This would not reduce the pricing of newly completed unsold stock, industry sources said.

I thought we would be able to increase the price more, but haven’t.

Pace managing director Shane Wilkinson

When interest rates start falling – or when people have confidence about when they will decline – established prices will also pick up and more new development will begin, they said.

If land prices, which have fallen 15 per cent already, declined a further 10 per cent, more new projects would kick off, Mr Wilkinson said.

But for now, he’s pushing ahead. In north-western Melbourne’s Flemington, Pace has a sold 192 of the 313 units also planned for a $360 million residential development on the edge of the city’s most famous racecourse that is under construction and due to complete in November next year.

After taking the project off market and relaunching it, he’s only been able to increase the average price of apartments in The Darley from $10,000 per square metre to $10,500.

“I thought we would be able to increase the price more, but haven’t,” Mr Wilkinson said. “The new world hasn’t arrived.”